I have interviewed at least sixty leading climate scientists in a dozen countries over the past three years. They are unanimously terrified by the speed at which things are moving, but also relieved that the crisis is finally getting some serious attention from both the public and the governments.

What might be useful at this point is a review of how the science has developed, because it can be seen as a play in three acts. In the first act, beginning in the 1980s, a warning was identified as a potentially serious problem, but not one that required an emergency response.

Yes, greenhouse gases of human origin were warming the atmosphere, but it could be dealt with by modest reductions in emissions (5%) by the biggest emitting countries. Developing countries could emit as much as they liked: it wouldn’t be enough to do any harm.

That was the 1990s. Twenty years on, in 2015, things had changed a lot. The early support for the notion that ‘something must be done’ had been undermined by a powerful campaign of climate change denial largely funded by the oil, gas and coal industries.

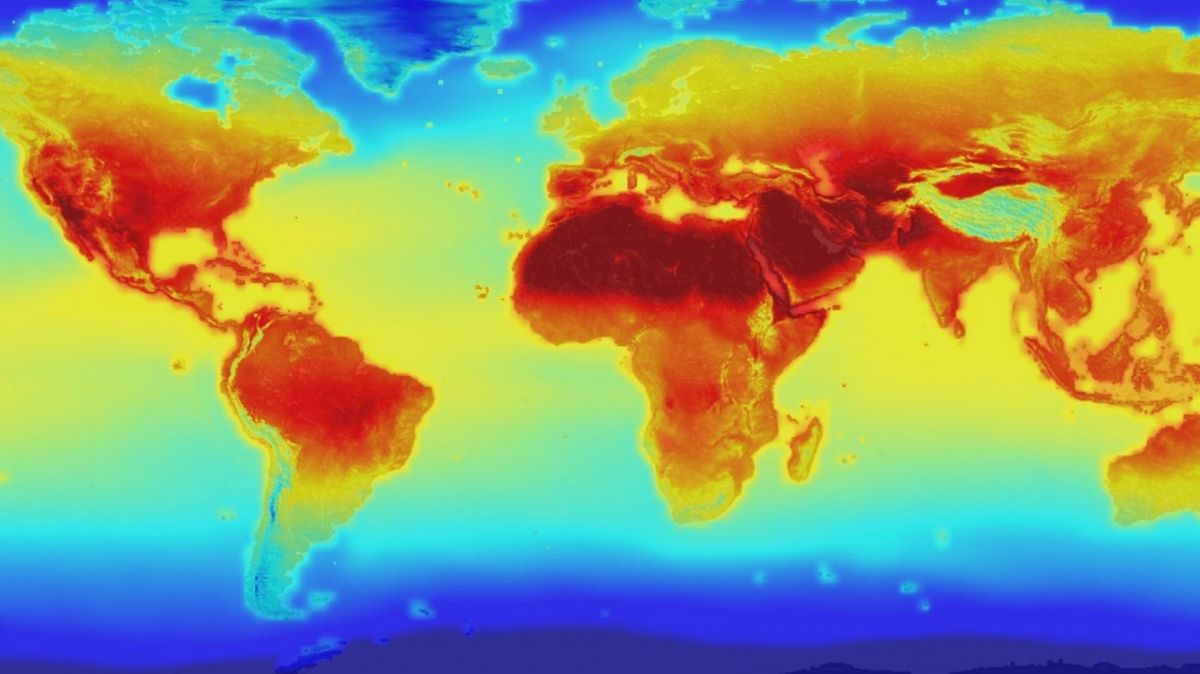

At the same time, the emissions of the ‘developing countries’ had soared as their economies shifted into high-speed growth. The biggest emitter is now China, not the United States, and India holds third place. Scientific understanding of how the atmosphere will react to a huge input of carbon dioxide and other warming gases has expanded enormously.

It has also become clear that the climate can change abruptly as well as gradually. As the climate warmed up when we emerged from the last Ice Age, it made sudden leaps when various ‘tipping points’ were crossed. Our warming is starting from an already much warmer climate, but we will almost certainly cross some tipping points too.

We have to stay below them at all costs, because we would have no way of turning them off once they got going. Johan Rockstrom, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Change Research that did most of the work on tipping points, sees our experience as a kind of journey.

“Thirty years of climate science has given us so much understanding, and what I now see very clearly as a red thread during that entire journey is that the more we learn about the Earth System, the more reason for concern we have....

“In 2001, you see the best assessment of the risk of crossing catastrophic tipping points, of destabiising the biosphere, is estimated to lie somewhere between +5°C and +6°C of warming.

“Then for every new assessment the level of average global temperature at which the risk of crossing tipping points gets serious just goes down, down, down – until 2018, when the assessment is somewhere between +2°C and +3°C.

“People think we raise the alarm because human pressures are increasing, but that’s not the case at all. It’s just that we are learning how the planet works, and the more we learn the more vulnerable she is.”

So here we are in 2023, and Jim Hansen, the climate scientist who delivered the original wake-up message to the US congress in 1988, returns to tell us that he has used new data to work out the ‘equilibrium climate sensitivity’. The news is bad.

The ECS – how much warming we will get in the long run from doubling the amount of carbon dixide in the atmosphere – is much higher than we thought. We were expecting an extra three degrees; we will get five.

In the short run, we also have an urgent problem from the opposite direction. Hensen reckons that all the visible pollution we put into the sky was cooling the planet by reflecting incoming sunlight back into space. About three degrees worth of cooling, so we would be in the deepest trouble imaginable without it.

But we are rapidly cleaning it up, because it’s bad for people’s lungs. In the past ten years, China got rid of 87% of the sulphur dioxide in the ‘brown cloud’ that used to hang over Chinese cities, a brilliant success – but events like that mean we are rapidly losing our protective global sunscreen.

In 2020 the International Maritime Organisation ordered all 60,000 giant container ships that carry 90% of the world’s trade to clean up their fuel. The permissible level of sulphur dioxide was cut from 3.5% to 0.5% – and the ‘ship tracks’, cloud cover that followed the ships like marine contrails – virtually disappeared.

Hansen suspects these changes have lost us one degree’s worth of cooling – and in terms of average global temperature a degree of lost cooling is just as bad as a degree of extra warming. It may be time to start taking this climate stuff seriously.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.